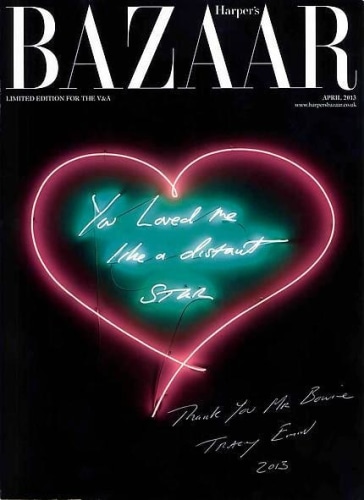

Rebel, Rebel

David Bowie's music was important to the artist Tracey Emin long before he became a friend. Here she rememberes their first encounters and describes the impact of his lyrics on her life

'Oh no love you're not alone... You're watching yourself but you're too unfair...' I sang the works at the top of my voice and took another swig of sherry.

'You got your head all tangled up but if I could only make you care.'

I was 14 and I wanted to die. With each mouthful of sweet acrid sherry, I was confident I was on my way. I sat with my feet against the wall and my back against my bed, savouring my last sights of this world.

'Oh no love you're not alone.'

I put the needle back to the beginning. 'Time takes a cigarette, puts it in your mouth.' Putting one of my 10 Rothmans to my mouth and lighting it, I drew on the cigarette dramatically, knowing it could be my last. I gulped back the last mouthful of sherry. I suddenly felt violently sick. I rushed to the landing and attempted to leap one flight to get to the bathroom. But it was no good. I just stood at the top of the stairs and projectile vomited.

Six months later I was packing a bag and leaving home. As far as I was concerned, I'd done my last school exams ever - the last exams in the whole universe for Tracey. And my only plan was to get away. I wasn't afraid. I wasn't running away. I was leaving. I filled up my holdall and I shoved two albums down the side: Pin Ups and Ziggy Stardust. I was 15. I wasn't sure where I was going or if there would be a record player there. But all I knew was I couldn't go anywhere in the world without Bowie.

Eighteen years later I was sitting in a restaurant with Carl Freedman, Matthew Collings, Georgina Starr and Gillian Wearing. We were fooling around, really giggling, when a shadow loomed over the table. A hand came towards me. Without looking up I shook it. In an instantly recognisable voice I heard the words: 'Hellow, my name's David Bowie, sorry to interrupt. But Tracey I'd just like to say I really appreciate your work.' I blushed and smiled and said: 'Yep, it's mutual. I really like yours too.' We fast became friends. He always seemed to have a knack for knowing things about me that no one should know - incredibly caring and intuitive. Whenever I spent time with him, I couldn't help but think of The Man Who Fell to Earth.

That November I went to Dublin with David and Iman. David was on his Earthling tour and I was going to interview him for an art magazine. We stayed at the Clarence Hotel. All night long, all I could here from outside my window was the chant: 'David, David, David.' David had said Dublin would be a good place to do the interview as the people there were very cool and not fussed by fame! The next day we went to Trinity College to see The Book of Kells. We stood in the queue. After about 10 minutes, David was recognised. A crowd started to gather round him and lots of people started asking for his autograph. 'Mr Boooieee, Mr Booooooieeee. If you could be so kind.' And it went on. Finally the security man came over to us and said: 'Mr Boooieee, if you would just like to come with me there's no reason for you to queue.' David tried to insist that we were fine queuing like everyone else. But it was quite obvious he wasn't like everyone else. The three of us were ushered in to view the sacred book. It was amazing. We stared down in silence, beyond the glass protecting the box, and focused on the marks across the pages. David was awe-struck. 'Incredible,' he kept saying. Then, as he raised his head to say something to Iman, a woman opposite him said: 'Jesus Christ, it's David Bowie,' and fainted.

We made jokes about who the real ancient relic was. 'But seriously,' I said to David, 'does it bother you, do you feel trapped?' In fact I asked about a million questions. About his smoking - he smoked about 60 cigarettes a day. He didn't drink, didn't take drugs, drank loads of coffee and like to haggle. We talked about blues music Jean Genet, 'Jean Genie', cut-ups, pop stars, glam rock, The Man Who Fell to Earth, Egon Schiele, Andy Warhol, New York, and the innocence of youth, his teeth, his painting and the future. I spent a fair bit of time explaining to him what a long-time admirer I was. I said: 'Christ, I don't know what I'd do if I just saw you over The Book of Kells. I don't think I would faint, but I might ask you for your autograph.' He said: 'No you wouldn't You'd say, "Hello David, I'm Tracey Emin!"

That night at the concert I stood in the sound box. One of the giant bodyguards said to me: 'Tracey, when I say the word "move", we move. You hold my hand and just come with me.' I heard the first few bars of 'Fame', then David shouted out to the audience: "This song goes out to my friend Tracey. She is going to be the most famous artist in the world.' I was already in another world and suddenly I heard the work 'move'. I held the giant bodyguard's hand as he pulled me through the crowd and onto the stage and down some back steps and into a blacked-out Mercedes van. I could hear the audience screaming, going wild, asking for more. The doors of the van opened and David and his bodyguards jumped in. The garage doors opened and we drove out. Hands and faces squashed agains the windows, pounding and banging like the Night of the Living Dead. I looked at David. He was very calm. I wondered to myself if this was his idea of people being cool and not fussed by fame.

The last time I saw David was in Spitalfields. He called to say he was in London and was coming round to see me sometime in the afternoon. He wanted to see my house because it was built by the Huguenots and he was interested in the history of Spitalfields. So rather than sit around and wait, I made myself busy by putting some curtains up on the ground-floor windows. I was up a ladder putting the second one up, when the doorbell rang. I looked out of the window - couldn't see anyone. No car, no driver, no taxi - it couldn't be David. I jumped down, opened the door and there he stood. I said to him: ' How did you get here?'

'By Tube,' he said. I looked at him unbelievingly. He said, 'Yes. I often travel by Tube. I wear a baseball cap and read a Greek newspaper. The most hassle I ever had was some guy saying to me, "Oi mate, has anyone ever told you you're a dead ringer for that David Bowie?"

Sometimes when I'm on the Tube I remember to look for him. His lyrics are in my soul and have been since the age of 10. Like and imprint that always makes me feel stronger. More romantic, more creative, less mad and more special.

'Oh no love you're not alone.

No matter what or who you've been.

No matter when or where you've seen.

All the knives seem to lacerate your brain.

I've had my share, I'll help you with the pain.

You're not alone...

You're wonderful.'

(All lyrics from 'Rock 'n' Roll Suicide')