September/October 2008

A Space For History And Hope

Vietnamese-Japanese artist fun Nguyen-Hatsushiba is considered by many to be one of the most innovative and impressive artists working in the contemporary art world today. As the curator Roger McDonald has observed, "In Nguyen-Hatsushiba's video pieces we encounter a space for history which seems endless and potent - another ground from which voices and hopes may be heard."

By Priya Malhotra

Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba's work is so ceaselessly imaginative, profoundly absurd, mesmerizingly dramatic, and impossibly physical that viewers cannot help but marvel at the talent of this artist who is best known and, rightly so, for his series of videos depicting men performing laborious tasks like hauling Vietnamese pedicabs or big New Year's Eve dragons through the sea. Flush with metaphors and allusions pertaining to Vietnamese history, particularly the Vietnam War and the plight of the "boat people," the myriad Vietnamese who fled their country in crude boats in the 1970s because they feared persecution from the Communist-controlled government after America and the South Vietnamese government lost the War in 1975, Nguyen-Hatsushiba's work is very much rooted in time and place, yet also easily transcends those specificities. The powerful image of men pulling pedicabs or cyclos, as they are known in Vietnam, underwater without any modern gear or apparatus references the struggles faced by the poor drivers of cyclos, some of whom were forced into this profession after the War, and those of the boat people who tried to flee. But, it can also be seen as an analogy for the work Vietnam, now one of the world's fastest-growing economies, is currently doing to reconcile the forces of modernization and industrialization. The endeavor of the cyclo drivers can also serve as a metaphor for anyone who has left their homeland in risky conditions, and, if one stretches the symbolism further, can also be seen as a metaphor for anyone anywhere, who has struggled in any way. Although there are specific political, historical, and cultural references in Nguyen-Hatsushiba's art, which also includes installations and performance pieces, they are typically obscure and allegorical and there is never any trace of didacticism in his mysterious, sometimes overly elusive creations. His videos tend to be magical and cinematic, recalling the likes of American video art pioneer Bill Viola, Iranian-American artist Shirin Neshat, and Japanese artist Hiraki Sawa. With their lofty themes and extravagant execution, all of Nguyen-Hatsushiba's works are definitely grand, and there is even something somewhat Shakespearean in their sweeping tragic-comic vision of human experience.

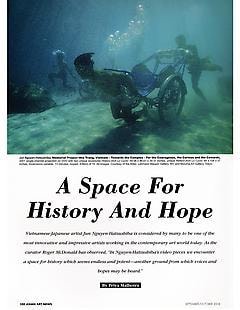

Born in Japan to a Vietnamese father and Japanese mother, Nguyen-Hatsushiba, 40, grew up primarily in the United States before moving to Ho Chi Minh City in 1996. He catapulted onto the global art stage at the Yokohama Triennial, in 2001 with Memorial Project Nha Trang, Vietnam: Towards the Complex - For the Courageous, the Curious, and the Cowards (2001), the video with men (fishermen in real life) ferrying cyclos underwater. It was the first of his four underwater memorial videos and is currently on view at the Asia Society in New York. Since 2001, he has shown at numerous international art exhibitions, including the Venice Biennial, Sao Paolo Biennial, and the Gwanju Biennial, and is represented by the Lehmann Maupin Gallery in New York. By creating transient memorials that are down in the sea, instead of a striking, static monument that looks up to the sky, commanding the respect and awe of the public, Nguyen-Hatsushiba has turned the idea of the traditional memorial on its head. And by doing so, he is asking many important and relevant questions. Does a memorial have to be a state-funded and state-managed structure rather than something personal and subjective? Is a memorial that is fluid and murky closer to the changing, ambiguous nature of memory rather than a concrete statue? Is an open-ended memorial that can be interpreted in different ways maybe a better way to remember an historical event that affected thousands of people rather than a monolithic memorial that tells the official story? Do we always have to be respectful and deferential when faced with a memorial? In Memorial Project Nha Trang, Vietnam, resisting the impulse towards glorification as always, the artist acknowledges the complexity of the boat people he is seeking to commemorate, by describing them, as the title suggests, as the Courageous, the Curious, and the Cowards. His portrayal is true to its title. As you watch men pulling cyclos in the sea, evoking the travails of the boat people, it arouses different reactions in the viewer. On the one hand, you might admire the courage and laud the effort of the men performing these difficult tasks, or you might feel sorry for them, or you might think they're crazy to actually do this. Similarly, you might think of the boat people who left their country not knowing whether they would survive the journey or even have a better life elsewhere as brave, wretched, insane, or a combination of all of those qualities.

One of the most compelling aspects of Nguyen-Hatsushiba's art, always elaborate and painstaking, is his portrayal of the scope and capacity of human beings to strive and labor, as well as the extent of the absurdity and futility of endeavor of any sort, including artistic endeavor. He seems to view the tireless efforts of human beings as both heroic and crazy, painting them as majestic tragic-comic figures in a grand drama. In Memorial Project Nha Trang, Vietnam, there seems to be no rational reason why the men are so arduously ferrying the cyclos in the sea. In Ho! Ho! Ho! Merry Christmas: Battle of Easel Point - Memorial Project Okinawa (2003), a group of men, dressed in elaborate scuba gear and gun belts with tubes of paint, valiantly travel to the bottom of the sea with their easels and attempt to paint in the water with great gusto. But, the images barely stay and the paint keeps disappearing into the water in big clouds of yellow. In his latest project, Breathing is Free 12756.3, which started last year and will take about six years to complete. Nguyen-Hatsushiba is running 12,756.3 kilometers, the diameter of the earth, in different cities in the world as an offering to all those who have had to flee their homelands. "It's a real struggle, not a performance," wrote Nguyen-Hatsushiba in a 2007 catalog essay published by Museum of Art Lucerne and Manchester Art Gallery. Even this smacks of both lofty ambition and certain madness.

All of Nguyen-Hatsushiba's work is suffused with a powerful poetry and sensuality with lush aquamarine waters, magical movements, and the dramatic use of light and color. In his videos, he also uses enthralling soundtracks, typically composed by him and Vietnamese pop music composer Quoc Bao, that keenly enhance the mood of the pieces. Of all his works the most poetic is Memorial Project Nha Trang, Vietnam, where you can see patterns of light quivering on the gorgeous water, shots of bubbles gushing in the sea, and the rocky seabed appearing before you like a magnificent, magical landscape. Men's bodies, the only underwater video in which they are unaided by fancy-looking gear, look absolutely beautiful and as they propel the cyclos with empty passenger seats in a hypnotic balletic motion, often rising up towards the surface of the water to get some air and then going back down. The most affecting moment in the video is when the men abandon their cyclos and start swimming in the water like expert fish towards white tents made of mosquito netting at the bottom of the sea, a possible symbol of a memorial or final resting place for the boat people. Their dramatic leap away from the cyclos also suggests a letting go of the burden and struggles of the past, a step towards a freedom where the body can finally move unencumbered. This piece is also visually the least busy of all his videos, and, as a consequence, has a greater impact on its viewer. Happy New YearMemorial Project Vietnam II (2003), which references the Tet Offensive of 1968 when Communist North Vietnamese forces and their allies launched a series of surprise attacks on South Vietnam even though both sides had agreed to put down their arms during the celebration of the Lunar New Year, is a virtual fiesta of colors. In this video, a traditional yellow-and-maroon New Year dragon puppet, supported from below by seven divers, thrashes about underwater while another diver supports a fantastical Fate Machine, a heavy-looking skeletal orb densely packed with smaller orbs of different hues that the Master of Destiny rotating the Machine randomly shoots towards the surface of the sea. When the small capsules are discharged, they burst into clouds, rivers and fogs of color in a theatrically poetic gesture. The potential metaphors for these explosive capsules abound. They might be seen as the souls of the boat people who died on their journeys, their vibrant hopes and daring dissolving into the sea. They can also he likened to the fireworks that must have been exploding during the New Year festival before the attack or to the bright pools of blood that were shed once the attack occurred. Or they can be seen as metaphors for random gunshots in a war.

For those who like ethereal beauty, some sections of The Ground, the Root, and the Air: The Passing of the Bodhi Tree (2007), a video shot on land and water in Luang Prabang, Laos, exploring the relationship between tradition and modernity in Southeast Asian youth cultures, offers exquisite moving images in muted hues. You see mountains shrouded by films of mist, a cloud-covered sky that has an air of romance about it, and a bucolic-looking Mekong River on which boats carrying local art students painting the shifting landscape languorously make their way. There is something poetic about the idea of the students painting as they move, as images come in and out of view, possibly a metaphor for how human beings, constantly moving through time, can never fully capture the details of the moment and have to rely heavily on memory to apprehend reality. No two art students passing through the same landscape paint exactly the same image, harking back to the idea of the personal, subjective nature of memory and the question of whether an official memorial with a supposedly objective account of whatever event or people it is seeking to commemorate is complete or not.

Although segments of The Ground, the Root, and the Air are really good, the piece does not work as a whole. There's too much going on, the connections between the different chapters seem random and tenuous, and it is just too obscure. The video moves from shots of joggers in a sports stadium to scenes of art students on boats, interspersed with images of traditional Buddhist lanterns typically used during the Festival of Light in Luang Prabang. (In the same show at Lehmann Maupin in New York in 2007, there was a fabulous installation of slowly turning Festival of Light lanterns decorated with

cut-out silhouettes of Buddhist chambers of Hell that cast big, ominous shadows on the walls and mingled with live feeds from news channels like CNN that were projected onto the walls.) It is only when you read a long press statement about The Ground, the Root, and the Air that it starts to make some sense, but it does make you wonder why the artist would try to clutter so many different issues in one work and dilute its impact. According to the statement, the joggers refer to social and cultural value that Southeast Asian youth now place on an active lifestyle and brands like Nike. But, the joggers in the video are not wearing Nike, but shoes made by Meike, a Chinese company that has successfully imitated Western shoe brands, to point out how brands like Meike are affecting the popular culture of developing nations. The images of the lanterns are supposed to signify a centuries-long tradition in Lao culture, a stark contrast to the world of the joggers. And if that wasn't enough to deal with in one work, the scenes of the art students in boats refer to the irreversible passage of time, according to the statement. In the final climatic moment of the video, some of the art students jump out of their boats and swim towards the Bodhi tree, a sacred Buddhist symbol, while the rest continue on their boats, an allusion to the conflict between the past and present in this part of the world.

Memorial Project Minamata: Neither Either nor Neither - A Love Story (2002-2003), a four-channel video installation comprised of scenes underwater and on land, is even more obscure and confusing than The Ground, the Root, and the Air and is Nguyen-Hatsushiba's least effective memorial piece. It includes shots of children playing on land, swirls of orange, men holding hands underwater, a reclining woman seen through blowing mosquito netting, young people dancing, and animated cartoons. The video, though still hypnotic, like all of Nguyen-Hatsushiba's work, makes hardly any sense and the plethora of images only distract and disrupt the viewer. Even when you realize that Nguyen-Hatsushiba is referring to the Minamata Bay disaster in the 1950s and 1960s where numerous people either died or developed a severe nervous condition known as "Minamata disease" because of the mercury dumped into the Japanese bay by Chisso Corporation, and to Agent Orange, the toxic herbicide and defoliant used by the Americans in the Vietnam War, the piece still remains frustratingly elusive.

Even though Nguyen-Hatsushiba, like most artists, might have had a couple of missteps, he is still one of the most innovative and impressive artists working in the contemporary art world today. "In Nguyen-Hatsushiba's video pieces we encounter a space for history which seems endless and potent - another ground from which voices and hopes maybe heard," correctly observed curator Roger McDonald in a 2003 catalog essay published by Museo D'Arte Contemporanea Roma.

Priya Malhotra is the New York-based contributing editor for Asian Art News and World Sculpture News.